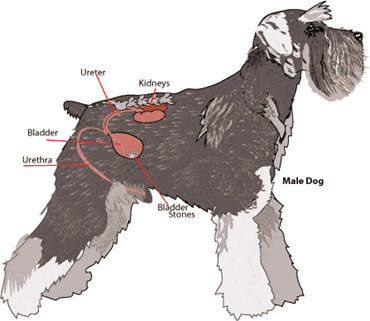

Urinary stones (urolith/ calculi) in the dog may occur anywhere in the urinary tract although approximately 85% occur in the bladder. There may only be one present but often multiple stones are seen.

Clinical signs

Dog with bladder stones generally have difficulty urinating and pass frequent small amounts of often bloody urine. This is because the stones in the bladder can rub against the bladder wall and irritate and damage the lining causing bleeding. In addition they can cause inflammation of the walls of the bladder and lining of the urethra (the tube that exits the bladder to the outside) which cause the dog to feel that they need to pass urine frequently. This can be a painful condition. If stones are present elsewhere in the urinary tract it may be more life threatening – either blocking the kidney draining, if present in the ureter (the tube connecting the kidney to the bladder) or blocking the bladder emptying if lodged in the urethra. Occasionally dogs may show no signs of discomfort.

Types of stones

There are various types of stones that may form in the urine. These are determined by the pH of the urine (if alkaline or acidic), the concentration of the minerals in the urine which is determined by diet and the amount of water your dog drinks, the genetics of your dog, and the presence of a urinary tract infection. Some examples are:

Struvite stones

These are composed of magnesium ammonium and phosphate minerals. These are commonly seen in Shih tzu, Miniature Schnauzers, Bichon Frise, Llhasa apso and Yorkshire terriers. Struvite minerals are a normal component of dogs urine, however if the urine becomes more alkaline and more concentrated, then the struvite crystals will precipitate out of solution and can eventually cause the formation of a struvite stone. This is often seen secondary to a urinary tract infection. Bacteria present in the urine produce urease, an enzyme that breaks down urea (a waste product) in the urine. This in turn releases ammonia, which makes the urine more alkaline and supplies more minerals to form crystals. The crystals often adhere to bacteria or cells from the bladder, and eventually multiple layers form a stone which can eventually grow to a few centimetres in diameter. Struvite stones are more common in bitches as the urethra is wider allow easier passage of bacteria into the bladder from the outside.

Calcium Oxalate stones

These are commonly seen in similar breeds to struvite stones but are more common in male dogs. These usually form in more acidic urine.

Urate stones

These are seen in Dalmations and bulldogs and are caused by a genetic defect of the dogs metabolism. This causes the production of higher levels of the substances in the urine that are the precursors to the urate stones.

Diagnosis

Occasionally with large or multiple stones, your vet may be able to palpate the stones through the bladder wall, but generally further diagnosis is needed. In most instances an x-ray of the abdomen will highlight the stones as they are often the same density as bone. However, occasionally some stones may not be visible on x-ray and an ultrasound may be required to visualise them. Your vet will also need a urine sample to check for the presence of blood, the pH, and look for evidence of crystals and to culture to check for a bacterial infection. In order to accurately diagnose which type of stone(s) is present then a sample of stone needs to be sent to the USA to check its composition – this is a free service run by Hills Pet foods. This sample can be obtained if the dog passes a small stone through the urethra in the urine, or if it is removed surgically. However your vet may make an educated guess as to the type of stone present in view of your dogs breed, the pH of your dog’s urine and the presence of crystals in the urine.

Treatment

Medical dissolution

Struvite stones can be dissolved medically. In order to achieve this your dog needs to be feed an exclusive diet that has low amounts of the constituents of the stones, lowers the pH of the urine, contains low protein levels (less urea in the urine for the bacteria to break down) and encourages the dog to drink more water (often with increased salt levels). In addition as the stone often contains layers of bacteria, your dog will need to stay on antibiotics for the duration of the treatment. In can take a number of weeks for dense stones to eventually break down and be passed in the urine. Repeat x-rays are needed every 3-4 weeks to ensure that the treatment is working.

Urohydropropulsion

This is a technique where your dog is anaesthetised, the bladder filled with saline and then the bladder is squeezed with the dog in an upright position to flush the stones out. This is only successful with female dogs which have a larger urethra and dogs with small stones present.

Surgery

This is indicated for dogs with stones not amenable to medical dissolution, male dogs with a risk of blocking the urethra, stones that are failing to break down medically (they can often can be layered with different minerals) or if a quicker recovery is required. Your dog is anaesthetised, the abdomen opened and a small hole is made in the bladder to remove any stones. In addition any stones should be flushed up the urethra back into the bladder prior to closing the bladder wall to ensure all stones are removed. Your dog can generally go home the same day and they tend to recover quickly.

Regardless of the type of stone present, recurrences are common and your dog will often need to be on a special diet lifelong or he/she may need regular monitoring with x-rays or urine sample.